Vaccines: What you need to know

Ryan Bailey, Contributing Writer

The vax, the myth, the legend. It’s simple to take yet hard to explain.

While it may seem like everyone already knows how vaccines work, there are common misconceptions that concern and dissuade some people from considering them.

Randall Moss, a professor of biology, knows a thing or two about the necessity of vaccines.

“Viruses aren’t technically living organisms,” Moss said. “They’re not cellular, they’re don’t self-replicate, they don’t have metabolism… it’s harder to kill something that’s not alive.”

Vaccines do not come lightly; teams of scientists and medical experts worldwide conduct at least 10 to 15 years of research before anything gets to the public. This research involves identifying an antigen that can prevent a disease. An antigen is a toxic substance, including bacteria and viruses, and is the part of a germ that our immune system recognizes and produces antibodies against.

If the United States Food and Drug Administration clears the research for further study, volunteers test the vaccine effectiveness and are monitored for side effects. This can take a few years.

At the next stage, thousands upon thousands of volunteers test the vaccine. At this point, it is known what dosage to give.

The FDA heavily monitors approved vaccines and analyzes data to ensure it is safe for the public.

What goes into a typical vaccine? For starters, the antigen is already killed or disabled. There’s no risk of illness from a dead antigen. Vaccines also contain preservatives, adjuvants that boost immune response, additives and residuals (antibiotics, etc.).

Efficiency wanes over time and some shots are not one and done.

“So things like the flu for example,” Moss said. “It’s so contagious, it’s so easily spread. Many strains of the flu even pass back and forth from animals.”

The flu needs a new vaccine every year because of this. It mutates quickly.

Not all vaccines are created the same. The Pfizer and Modern vaccines for COVID-19 protection are controversial for being the first widescale synthetic messenger RNA (ribonucleic acid) vaccines in use.

Every cell in our body produces billions of messenger RNAs. They deliver instructions to our ribosomes to make proteins. The coronavirus contains a spike protein, and the mRNA vaccines contain the instructions to create that spike protein.

Our immune system learns how to fight COVID-19 without having first contracted it.

No one should fret though, as they follow decades of research in their development. The COVID-19 vaccines weren’t whipped out from scratch, just adapted to the virus’ spike protein.

Messenger RNA technology is seeing good signs in other ventures. For example, a flu shot that may cover most influenza viruses has been found to be effective in animal trials.

It’s still not the typical vaccine technology in use, and some are concerned it’s too new.

For example, a bill was recently introduced in Idaho that would ban administering mRNA vaccines.

The controversy of these vaccines has given rise to mass skepticism about adverse effects to the body from vaccines. Skepticism has stalled diseases such as measles from being fully eradicated. The disease passes between unvaccinated individuals in a community.

Vaccines contain no toxic ingredients, and any ingredient, such as formaldehyde or aluminum, that could potentially be is such a tiny amount it is harmless.

People who are vaccinated against a disease can still be infected as no vaccine is entirely effective. Some individuals do not develop immunity, but most do.

The higher the number of vaccinated individuals, the lesser the chance a disease can spread.

Statistically, vaccine complications are incredibly rare, and most events are not due to the vaccine itself. They are usually from an ingredient the individual is allergic to.

Moss said anytime there is an allergic response to a vaccine, it must be reported, and they document it to keep record [Centers for Disease Control and Prevention].

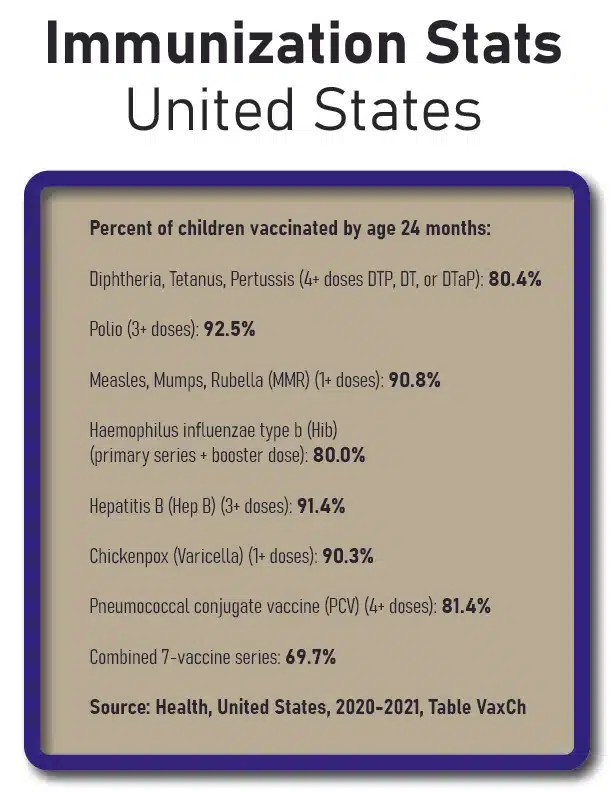

Many diseases can be prevented through a shot. For example, Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib) may cause brain damage, deafness and death. The virus is 99% eradicated today because of vaccination.

Between the 1950s and 1970s, the World Health Organization tackled smallpox worldwide with the vaccine. Smallpox went from having killed hundreds of millions of people to being wiped from existence since 1980.

Through these campaigns, transmission of diseases like mumps, rubella, and diphtheria has fallen as much as 99% since the 20th century.

“The virus that causes polio is gonna be much less contagious,” Moss said. “It’s not spread as quickly. We have a vaccine that works incredibly well for polio, so it’s not going to mutate much if at all.”

Replication leads to mutation. Vaccines that prevent infection block replication.

The best way to make sure you’ll be completely safe taking a vaccine?

“I would say ask your doctor or visit the CDC’s website,” Moss said.